When townfolk visit us at The Big C Ranch (my name for Brigham and Women’s Hospital), a little clumsiness is forgivable. We were flummoxed when we were diagnosed; so are they, and they try to comfort us in the best ways they know how.

Our grandmas, bless’em, arrive with brimming pots still warm from their stoves. They don’t want to hear from smarty-pants doctor talk like “immunocompromised” and “outside contaminants.” Grandma keeps a clean kitchen, she knows what her ragazzino/bubeleh/niñito needs, and it’s her meatballs and gravy/matzo soup/chiles en nogada. She’s trying to save your life—nothing less.

Your humor’s a bit thin, but the “laughter is the best medicine” sort believes he’s helping when he jokes, “When your body hair grows back, you can brag about getting your pubes all over again! Aw c’mon! That was a good one!”

The scoffers mistake it for comfort when they belittle our modesty and senses of loss. They snort, wave a dismissive hand and say “It’s just hair! It’ll grow back!” Well, scoffer, if it’s “No big deal!” and I should “Just let them do it,” then let a nurse swab your damned rectum for C-Diff bacteria.

The malignant.

A clumsy person may be forgiven; a malignant one must be shunned. We’re stocked up on malignancy, and I’ve observed six “supporters” who will drain the life from you, heedless of how short that life may be. (I wasn’t tasked by these pestilent six, but agonized while friends suffered them.)

The Ghoul thrills to the details of your suffering. How bad is the surgical scar? Does the chemo make you vomit? What’s the most embarrassing part of it all? “I only ask because I care,” but how long do you have to live? Would dearly like to see the blood clot the size of a baby’s finger that you sneezed up this morning.

The Smartest Guy in the Room undermines your confidence in your healers. He has their number. Lapses into stony silence whenever one of “them” (e.g., a nurse checking your vitals) enters your room. Sneers at Western Medicine and Big Pharma (crooked and in cahoots), but believes in cannabis and any cure that originated centuries ago, in India or eastward.

Forgive the clumsy, but shun the malignant. You’re stocked up on malignancy.

The Prodigal Father never paid child support, and missed your wedding. Learned about your cancer through the one cousin who still talks to him. But “I’m here now. And no one—especially That Mother of Yours—can say Joey Buttaroma doesn’t love his little girl.”

The Chemo-Sabe clings to you like Tonto to The Lone Ranger. Demands to know who visits you most often, and visits one time more. A gossip who won’t leave until you’re angry with someone else. Declares himself/herself shocked that Paul/Nancy/Carla/Phil hasn’t come to see you! But where Paul and Nancy have failed you, the Chemo-Sabe never will.

The Gatekeeper is often the sibling or cousin with whom you got along least. But she’s here now, to protect you from everyone else (“She needs her rest, so no one gets to her unless it’s through me. That goes for even you, Ma.”). Insists “You and me. We’re gonna beat this thing, together.”

The Serpent offers to sneak in wine, a Subway foot-long BLT, marijuana in brownies, because “You’ve been through Hell, you deserve it!” Never mind the life-threatening risks of salmonella or drug interactions—“Doctors have to tell you that stuff.” Will take you straight to a bar to “cut loose” once you’re released. Like The Gatekeeper, tries to get between you and others (viz., “Don’t tell that judgmental brother of yours, he doesn’t know how to live”).

You’re in need, but they are needier.

“It’s not your blood they drain; it’s your emotional energy,” wrote Dr. Albert J. Bernstein, who reckoned demons like these in his 2001/2012 book Emotional Vampires: Dealing with People Who Drain You Dry.

What do they need from you?

- The Ghoul seeks the kind of thrills that can only be got from human suffering. May not be a sociopath, but has all the sensitivity of one. Will lose interest in you when you are cured.

- The Smartest Guy in the Room needs you to acknowledge his superiority, even in a hospital like Brigham and Women’s surrounded by healers who never got an A-.

- The Prodigal Father needs your validation that he hasn’t failed as a parent, which only you can grant. He’ll then wave that knowledge under the nose of That Mother of Yours.

- The Chemo-Sabe is likely awkward, friendless, and you are a zoo animal that she can visit at will.

- The Gatekeeper’s devotion to you proves his/her value to those who (often rightly) question it.

- The Serpent is usually a sociopath, bent on punishing you for the sin of courage, or for pulling attention.

They likely mistake their ill intent for good, as the emotional vampire is usually an horrendously poor self-observer.

Strategies to protect yourself.

Ask yourself simply, whose visits do you anticipate, and whose do you dread? Make a two-column list, and be merciless. Only you will read it.

Whose visits do you anticipate? And whose do you dread?

Having discerned between the two, there are several actions you can take:

- Surrender your need to please. Easier to say than to do. But The Ghoul, The Prodigal Father and The Serpent have no feelings to hurt.

- Tell them, “Please don’t come, I need to rest.” This is no lie. You do need rest, and visits from The Ghoul and Chemo-Sabe aren’t restful.

- If you are unassertive, enlist someone who is. Perhaps in your emotionally wrung-out state, you can’t bring yourself to confront The Gatekeeper by saying “You’re not in charge of who sees me, I am.” Then ask your warhead of a sister/brother/best friend/mom/spouse to say it for you. They’d be delighted.

- Enlist your nurses as bouncers. They are charged with your wellbeing—physical and emotional. Tell them, simply, “I’m expecting my parents today; please don’t admit anyone else.”

Jeez, isn’t that really judgmental?

No. It is discernment. Surrounding yourself with healing energy, and protecting yourself when you must.

As a kid, did a friend give you your first cigarette? Sneak a Budweiser out of your dad’s six-pack? Maybe get you to shoplift? Your parents likely demanded you drop that friend. They didn’t wast time “hating the sin, but loving the sinner.” Their child was imperiled, and they acted. They let God sort out the sinner.

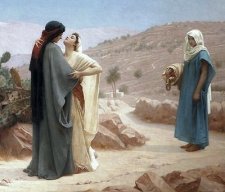

That is discernment, and both the Old Testament and New teach us to protect ourselves from the ill-meant:

- “And whosoever will not receive you, when ye go out of that city, shake off the very dust from your feet for a testimony against them.” (Luke 9:5.) Jesus taught, if you are not heard—and these six are deaf to what you truly need—then disengage.

- “I have not sat with vain persons, neither will I go in with dissemblers.” (Psalm 26:4.) Dissemblers are liars, and “dis-assemblers” who come between you and others.

- “He that goeth about as a talebearer revealeth secrets: therefore meddle not with him that flattereth with his lips.” (Proverbs 20:19.) A gossip, like the Chemo-Sabe, is a talebearer.

- “Avoid profane and vain babblings, and oppositions of [knowledge] falsely so called.” (1 Timothy 6:20.) This applies to The Smartest Guy in the Room, especially, who wants to shake your faith in your treatment.

- “But shun profane and vain babblings: for they will increase unto more ungodliness.” (2 Timothy 2:16.) Simply put, shut down a liar, dissembler or gossip immediately; your further corruption is their joy.

You have the permission of Christ, King David, King Solomon and the Apostle Paul to protect yourself.

With the chaff sorted out, we are left with the wheat; those whose visits leave us feeling energized, optimistic, healed. On my list “Lifts My Spirits” were my parents, my Sadie Mae, her magnificent brothers and their wives, alongside my old pals Bill, Erik and Frank.

There were but two names on my list “Leaves Me Drained,” each with the same flaw—a mean temper. After her latest tantrum, over grammar (she teaches writing at a university), I definitively told one, “Do not visit, do not phone, and I’ll update you if I survive.” I repent of my sarcasm. But I’d been trapped alive in the Big C bunkhouse for a seven-week round of chemo, with almost four weeks to go, and no guarantee of survival.

Those are the stakes, no less. We need our depleted energy for survival. I wouldn’t risk a minute of life with Sadie Mae, arguing with someone else if “thusly” is a word.

You have the permission of Christ, King David, King Solomon and the Apostle Paul to protect yourself from emotional vampires. Please, do. Trust in God; He’ll sort’em out.

Godspeed.